The Hunting of the Snark

Cover of first edition | |

| Author | Lewis Carroll |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Henry Holiday |

| Cover artist | Henry Holiday |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Nonsense poetry |

| Publisher | Macmillan Publishers |

Publication date | 29 March 1876 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| OCLC | 2035667 |

| Text | The Hunting of the Snark at Wikisource |

The Hunting of the Snark, subtitled An Agony, in Eight fits, is a poem by the English writer Lewis Carroll. It is typically categorised as a nonsense poem. Written between 1874 and 1876, it borrows the setting, some creatures, and eight portmanteau words from Carroll's earlier poem "Jabberwocky" in his children's novel Through the Looking-Glass (1871).

Macmillan published The Hunting of the Snark in the United Kingdom at the end of March 1876, with nine illustrations by Henry Holiday. It had mixed reviews from reviewers, who found it strange. The first printing of the poem consisted of 10,000 copies. There were two reprints by the conclusion of the year; in total, the poem was reprinted 17 times between 1876 and 1908. The poem also has been adapted for musicals, movies, opera, plays, and music.

The narrative follows a crew of ten trying to hunt the Snark, a creature which may turn out to be a highly dangerous Boojum. The only crew member to find the Snark quietly vanishes, leading the narrator to explain that the Snark was a Boojum after all.

Carroll dedicated the poem to young Gertrude Chataway, whom he met in the English seaside town Sandown on the Isle of Wight in 1875. Included with many copies of the first edition of the poem was Carroll's religious tract, An Easter Greeting to Every Child Who Loves "Alice".

Various meanings in the poem have been proposed, among them existential angst, an allegory for tuberculosis, and a mockery of the Tichborne case.

While Carroll denied knowing the meaning behind the poem,[1] he agreed in an 1897 reply to a reader's letter with an interpretation of the poem as an allegory for the search for happiness.[2][3] Henry Holiday, the illustrator of the poem, considered the poem a "tragedy".[a]

Plot

[edit]Setting

[edit]The Hunting of the Snark shares its fictional setting with Lewis Carroll's earlier poem "Jabberwocky" published in his 1871 children's novel Through the Looking-Glass.[5] Eight nonsense words from "Jabberwocky" appear in The Hunting of the Snark: bandersnatch, beamish, frumious, galumphing, jubjub, mimsiest (which previously appeared as mimsy in "Jabberwocky"), outgrabe, and uffish.[6] In a letter to the mother of his young friend Gertrude Chataway, Carroll described the domain of the Snark as "an island frequented by the jubjub and the bandersnatch – no doubt the very island where the jabberwock was slain."[7]

Characters

[edit]The crew consists of ten members, where all but one description of the members begin with the letter B:[8] a Bellman, the leader; a Boots[b] (the only member of the crew without an illustration);[10] a maker of Bonnets and Hoods (the only description which does not begin with the letter B); a Barrister, who settles arguments among the crew; a Broker, who can appraise the goods of the crew; a Billiard-marker, who is greatly skilled; a Banker, who possesses all of the crew's money; a Beaver, who makes lace and has saved the crew from disaster several times; a Baker, who can only bake wedding cake, forgets his belongings and his name, but possesses courage; and a Butcher, who can only kill beavers.[11]

-

Bellman

-

maker of Bonnets and Hoods

-

Barrister

-

Broker

-

Billiard-marker

-

Banker

-

Beaver

-

Baker

-

Butcher

Summary

[edit]

After crossing the sea guided by the Bellman's map of the Ocean (a blank sheet of paper) the hunting party arrives in a strange land, and the Bellman tells them the five signs by which a snark[c] can be identified. The Bellman warns them that some snarks are highly dangerous boojums; on hearing this, the Baker faints. Once revived, the Baker recalls that his uncle warned him that if the Snark turns out to be a boojum, the hunter will "softly and suddenly vanish away, and never be met with again".[15] The Baker confesses that this possibility terrifies him.

The hunt begins:

Along the way, the Butcher and Beaver, previously mutually wary, become fast friends after they hear the cry of a jubjub bird and the Butcher ends up giving the Beaver a lesson on maths and zoology. The Barrister, meanwhile, sleeps, and dreams of witnessing a court trial of a pig accused of deserting its sty, with a snark as its defence lawyer.

During the hunt, the Banker is attacked by a bandersnatch, and loses his sanity after trying to bribe the creature.

The Baker rushes ahead of the party and calls out that he has found a snark, but when the others arrive, he has mysteriously disappeared.

They hunted till darkness came on, but they found

Not a button, or feather, or mark,

By which they could tell that they stood on the ground

Where the Baker had met with the Snark.

In the midst of the word he was trying to say,

In the midst of his laughter and glee,

He had softly and suddenly vanished away—

For the Snark was a Boojum, you see.[17]

Development

[edit]Two explanations of which event in Carroll's life gave rise to The Hunting of the Snark have been offered. Biographer Morton N. Cohen connects the creation of The Hunting of the Snark with the illness of Carroll's cousin and godson, the twenty-two-year-old Charlie Wilcox.[18] On 17 July 1874, Carroll travelled to Guildford, Surrey, to care for him for six weeks, while the young man struggled with tuberculosis.[19][20] The next day, while taking a walk in the morning after only a few hours of sleep, Carroll thought of the poem's final line: "For the Snark was a boojum, you see."[21]

Fuller Torrey and Judy Miller suggest that the event that inspired the poem was the sudden death of Carroll's beloved uncle, Robert Wilfred Skeffington Lutwidge, caused by a patient in 1873 during Lutwidge's time as an inspector of lunatic asylums. They support their analysis with parts of the poem, such as the Baker's uncle's advice to seek the snark with "thimbles, forks, and soap", which, according to Torrey and Miller, were all items the lunatic asylum inspectors checked during their visits.[22]

Holiday and Carroll had some disagreements on the artwork. Carroll initially objected to Holiday's personification of hope and care, but agreed to the change, when Holiday explained that he had only intended to add another layer of meaning to the word "with".[23] However, Carroll refused his illustration of the boojum, preferring that the creature go without a depiction,[24] and made him change his initial portrayal of the Broker, as it could have been perceived as antisemitic.[10]

When finally published, the poem comprised 141 stanzas of four lines each,[25] with internal rhymes in the first and third lines of irregular stanzas appearing in the poem from the second fit onwards.[26] Martin Gardner[27] annotated to The Hunting of the Snark that Elizabeth Sewell pointed out in The Field of Nonsense (1973) that a line in Carroll's poem has a similarity to a line in a limerick ("There was an old man of Port Grigor...") by Edward Lear.

Illustrations

[edit]To illustrate the poem Carroll chose Henry Holiday, whom he had met in 1869[23] or 1870.[28] At the time Carroll approached him to ask if he could create three illustrations for the poem, Carroll had completed three "fits", as he called the parts of his poem – fit can mean either canto or convulsion[29] – "The Landing", "The Hunting", and "The Vanishing".[28] He intended to title it The Boojum and include it in his fantasy novel Sylvie and Bruno, which was unfinished at the time.[28] However, in late October 1875, Carroll thought about having it published during Christmas; this proved impossible, as the wood engraving for the illustrations needed three months to be complete.[30] By the time Holiday had completed the sketches and sent them to Carroll, Carroll had already created a new fit requiring an illustration. They worked this way until Holiday had created nine illustrations as well as the front cover and the back cover of the book.[23] Thus, among the ten illustrations shown below, one illustration is not by Holiday.[31] The "Ocean Chart" is typographic art whereas electrotypes made from Joseph Swain's woodblock engravings were used to print Holiday's illustrations.

-

The Bellman landing the Banker by entwining a finger in the Banker's hair

-

The Butcher (left) and the Beaver (right) looking sideways

-

The ocean chart (which is blank)

-

The Baker whose belongings were left behind on the beach

-

The Butcher doing maths

-

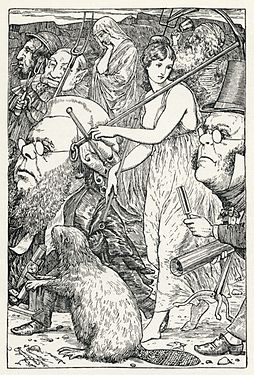

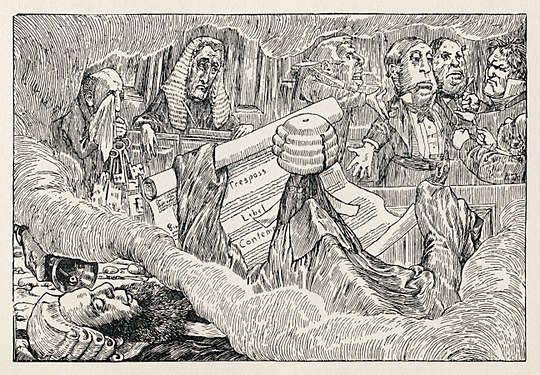

The Barrister's dream of the trial of the pig, with the Snark shown draped in a cloth in the foreground acting as defence barrister; the Bellman's bell is ringing in his ear in the lower left

-

The Bellman, Banker, and Butcher holding the Beaver

There is no depiction of the Snark, nor of Boots. However, based on a draft[32] by Carroll, the snark was allowed to show up in an illustration by Holiday, where it appeared in a dream of the Barrister.

The illustration to the chapter The Banker's Fate might contain pictorial references to the etching The Image Breakers by Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder,[33] to William Sidney Mount's painting The Bone Player and to a photograph by Benjamin Duchenne used for a drawing in Charles Darwin's 1872 book The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals.[34]

Publication history

[edit]Girt with a boyish garb for boyish task

Eager she wields her spade: yet loves as well

Rest on a friendly knee, intent to ask

The tale he loves to tell.

Rude spirits of the seething outer strife,

Unmeet to read her pure and simple spright,

Deem, if you list, such hours a waste of life

Empty of all delight!

Chat on, sweet Maid, and rescue from annoy

Hearts that by wiser talk are unbeguiled.

Ah, happy he who owns that tenderest joy,

The heart-love of a child!

Away fond thoughts, and vex my soul no more!

Work claims my wakeful nights, my busy days—

Albeit bright memories of that sunlit short

Yet haunt my dreaming gaze!

—Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark

Upon the printing of the book on 29 March 1876, Carroll gave away eighty signed copies to his favourite young friends; in a typical fashion, he signed them with short poems, many of them acrostics of the child's name.[30] He dedicated The Hunting of the Snark to Gertrude Chataway, whom he had befriended in summer 1875 at the English seaside town Sandown on the Isle of Wight.[35] He finished the dedication a month after befriending her, a double acrostic poem that not only spelled out her name, but contained a syllable of her name in the first line of each stanza.[36] The stanza of his first draft concluded "Rest on a friendly knee, the tale to ask / That he delights to tell."[7] The poem was printed in The Hunting of the Snark with permission from Chataway's mother.[7]

Included with many copies of the first edition of The Hunting of the Snark was Carroll's three-page, religious tract to his young readers, An Easter Greeting to Every Child Who Loves "Alice".[37][38] Largely written on 5 February 1876, An Easter Greeting explores the concept of innocence and eternal life through biblical allusions and literary allusions to Romantic writers William Blake and William Wordsworth.[18][37] Gardner suggests that Carroll included the tract as a way of balancing the dark tone of the poem.[37] Scholar Selwyn Goodacre speculates that, as many copies of first-edition of the poem contain the tract, there is a possibility that all first editions originally had a copy of An Easter Greeting.[39]

Reception and legacy

[edit]The first printing of The Hunting of the Snark consisted of 10,000 copies.[40] By the conclusion of 1876, it had seen two reprints, with a total of 18,000[41] or 19,000 copies circulating.[40] In total, the poem was reprinted seventeen times between 1876 and 1908.[41]

The Hunting of the Snark received largely mixed reviews from Carroll's contemporary reviewers.[20] The Academy's Andrew Lang criticised Carroll's decision to use poetry instead of prose and its too appealing title.[20] The Athenaeum described it as "the most bewildering of modern poetry", wondering "if he has merely been inspired to reduce to idiotcy as many readers and more especially reviewers, as possible".[20] According to Vanity Fair, Carroll's work had progressively worsened after Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), with The Hunting of the Snark being the worst of his works and "not worthy [of] the name of nonsense".[20] While The Spectator wrote that the poem's final line had the potential to become a proverb, it criticised the poem as "a failure" that might have succeeded with more work from the author.[20] The Saturday Review wrote that the poem offered "endless speculation" as to the true identity of the Snark, although the unnamed reviewer felt that the familiar nature of Carroll's nonsense weakened its effect for the reader.[20] Conversely, The Graphic praised the poem as a welcome departure from the Alice books, and called it "a glorious piece of nonsense", that could appeal to all Alice fans.[20]

"The Hunting of the Snark" has in common some elements with Carroll's other works. It shares its author's love of puns on the word "fit" with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland,[42] and mentions of "candle-ends" and "toasted cheese" with his supernatural poem Phantasmagoria.[43] Additionally all three works include the number "42".[44] Another of Carroll's children's novels, Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1893) makes a reference to the Boojum.[45]

Other illustrators of The Hunting of the Snark include Peter Newell (1903), Edward A. Wilson (1932), Mervyn Peake (1941), Aldren Watson (1952), Tove Jansson (1959), Helen Oxenbury (1970), Byron Sewell (1974), John Minnion (1974), Harold Jones (1975), Ralph Steadman (1975), Quentin Blake (1976), Frank Hinder (1989) and Brian Puttock (1997).[39]

Cultural impact

[edit]

The Hunting of the Snark has seen various adaptations into musicals, opera, theatre, plays, and music,[39] including a piece for trombone by Norwegian composer Arne Nordheim (1975)[47] a jazz rendition (2009),[48] and (in French translation – La chasse au Snark) with music by Michel Puig for five actresses, eight actors and an instrumental ensemble of five players, premiered at the Festival d'Avignon in 1971.[49] The poem was turned into a £2 million budget West End musical The Hunting of the Snark by Mike Batt. In 2023 a film was released by Simon Davison.[50][51]

The poem has inspired literature, such as Jack London's The Cruise of the Snark (1911),[39] the science-fiction short story "Chaos, Coordinated" (1947) by John MacDougal,[52] Elspeth Huxley's With Forks and Hope (1964)[53] and the title of Kate Wilhelm's novella "With Thimbles, with Forks and Hope."[54] American author Edith Wharton (1862–1937) was fond of the poem as a child.[52]

Additionally, it has also been alluded to in

- fiction, such as Perelandra (1943) by C. S. Lewis;[55] and Stand on Zanzibar by John Brunner; in the sci-fi novel Startide Rising (1983) and its sequels the spaceship Streaker is described as a Snarkhunter-class exploration vessel. In the Ocean of Night Benford it is rather prominent. In the 1966 short story "Jonah" ("Jonas" in French) by Gérard Klein, "snark" is a term used for bioships that go berserk.

- television, such as "The Soul of Genius" episode of the British TV crime drama Lewis[56]

- court rulings, such as in Parhat v. Gates (2008)[57]

- a phenomenon in superfluidity[58]

- graph theory[59]

- hydrology,[60] with a group of French hydrologists publishing in a well-known scientific journal a prose analogue to Carroll's poem, mocking the rivalries existing in the academic community

- geography, a Snark Island and Boojum Rock exist in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal

- botany, the Boojum tree in Baja California, Mexico[46] [61]

- Japanese animation, such as Ghost Hound (2007–08)[62]

- video games, such as Half-Life (1998)[63] and American McGee's Alice (2000)[64]

- A song, "Nine Funerals of the Citizen King", by Henry Cow.[65]

Analysis

[edit]

Various themes have been suggested by scholars. According to biographer Florence Becker Lennon, the poem's "motif of loss of name or identity" is typical of Carroll's work.[67] Richard Kelly writes that the poem contains a "theme of annihilation".[68] Furthermore, Edward Guiliano feels that the Snark is within the nonsense tradition of Thomas Hood and, especially, W. S. Gilbert, the librettist of the famous Gilbert and Sullivan team. According to him, a case can be made for a direct influence of Gilbert's Bab Ballads on The Hunting of the Snark, based on the fact that Carroll was well-acquainted with the comic writing and the theatre of his age.[69]

Widely varying interpretations of The Hunting of the Snark have been suggested: an allegory for tuberculosis,[70] a mockery of the Tichborne case, a satire of the controversies between religion and science, the repression of Carroll's sexuality, and a piece against vivisection, among others.[71] According to Cohen, the poem represents a "voyage of life", with the Baker's disappearance caused by his violation of the laws of nature, by hoping to unravel its mysteries.[72] Lennon sees The Hunting of the Snark as "a tragedy of frustration and bafflement", comparable to British actor Charlie Chaplin's early comedies.[73]

According to Kelly, The Hunting of the Snark is "Carroll's comic rendition of his fears of disorder and chaos, with the comedy serving as a psychological defense against the devastating idea of personal annihilation."[74] Kelly writes that the Bellman's Rule of Three ("What I tell you three times is true") and starting each character's name with the letter B are "notable attempts to create a sense of order and meaning out of chaos".[8]

F.C.S. Schiller, writing under the pseudonym "Snarkophilus Snobbs", interprets the poem as an allegory of Man's attempt to understand "the Absolute", and the members of the crew as representing different cultural approaches to the problem.[75] His interpretation of the Sixth Fit, "The Barrister's Dream" is particularly notable: He reads the trial of the pig for deserting its sty as symbolizing the ethical debate about whether suicide should be condemned as an immoral or culpable action. The pig who deserts its sty represents the suicidal person who abandons life. (Like the pig, he's guilty – but being dead, is not punishable.)

Martin Gardner sees the poem as dealing with existential angst,[76] and states that the Baker may be Carroll's satire of himself, pointing to the fact that the Baker was named after a beloved uncle, as was Carroll, and that the two were around the same age at the time of the writing of the poem.[77] Alternatively, Larry Shaw of the fan magazine Inside and Science Fiction Advertiser suggests that the Boots, being the Snark, actually murdered the Baker.[78][79]

Darien Graham-Smith suggests that The Hunting of the Snark stands for science (e.g. Charles Darwin's research), where the Boojum stands for religiously unsettling results of scientific research (e.g. Charles Darwin's findings).[80]

Also references to religious issues had been suggested, like the Baker's 42 boxes being a reference to Thomas Cranmer's Forty-Two Articles with a focus on the last article on eternal damnation,[81] and Holiday's illustration to the last chapter containing a pictorial allusion to Cranmer's burning.[82][83]

See also

[edit]

- Snark

- The Hunting of the Snark musical (1984–1986), written by Mike Batt based on the original poem.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Holiday's handwritten note on a letter from C.L. Dodgson: "L.C. has forgotten that "the Snark" is a tragedy ...".[4]

- ^ In his German translation of The Hunting of the Snark,[9] Günther Flemming assumes on p. 161 that "Boots" is a portmanteau word for "Bonnets and Hoods", and that therefore the Snark hunting party only consists of nine members, not of ten members.

- ^ Carroll did not give the word "snark" any meaning. The word "snarking" had been used in 1866 to describe a sound.[12] The word "snarky" was used to mean "crotchety or snappish" in the early part of the 20th century, but that usage was later replaced by its current meaning of "sarcastic, impertinent or irreverent";[13] that adjective in turn has been back-formed to the noun "snark", meaning "an attitude or expression of mocking irreverence and sarcasm".[14]

- ^ A reference to the Railway Mania of the time.[citation needed]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Gardner 2006, p. xxxvii.

- ^ Letter by C.L. Dodgson to Mary Barber, January 12, 1897: "To the best of my recollection, I had no other meaning in my mind, when I wrote it: but people have since tried to find the meanings in it. The one I like best (which I think is partly my own) is that it may be taken as an Allegory for the Pursuit of Happiness."

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. xxxviii.

- ^ "Lot 646: Carroll, Lewis [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson] The Hunting of the Snark: An Agony in Eight Fits. Macmillan, 1876". Sotheby's. 15 July 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ Lennon 1962, p. 176.

- ^ Lennon 1962, p. 242.

- ^ a b c Gardner 2006, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Kelly 1990, p. 67.

- ^ Günther Flemming, ALICE. Band 3: "Die Jagd nach dem Schnark (Lewis Carroll), ALICEANA & Essays zu Leben und Werk". Aus dem Englischen übersetzt und kommentiert, 668 pages, (Berlin, 2013) ISBN 978-3-8442-6493-7

- ^ a b Gardner 2006, p. 17.

- ^ Carroll 1898, pp. 8–14.

- ^ Anon (29 September 1866). "Sermons in Stones". Notes and Queries. Series 3. 10 (248): 248. doi:10.1093/nq/s3-X.248.248-f.

- ^ "Definition of Snarky". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ "Definition of Snark". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ Carroll 1898, p. 23.

- ^ Carroll 1876, p. 79.

- ^ Carroll 1876, p. 83.

- ^ a b Cohen 1995, p. 403.

- ^ Cohen 1995, pp. 403–404.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cohen, Morton N. (1976). "Hark the Snark". In Guilano, Edward (ed.). Lewis Carroll Observed. New York, NY: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. pp. 92–110. ISBN 0-517-52497-X.

- ^ Cohen 1995, p. 404.

- ^ Torrey, E. Fuller; Miller, Judy (2001). The Invisible Plague: The rise of mental illness from 1750 to the present. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 0-8135-3003-2.

- ^ a b c Holiday, Henry (2006). "Excerpts from Henry Holiday's Reminiscences of my Life". In Gardner, Martin (ed.). The Annotated Hunting of the Snark: The definitive edition. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 113–115. ISBN 978-0-393-06242-7.

- ^ Clark 1979, pp. 196–97.

- ^ Kelly 1990, p. 22.

- ^ Lennon 1962, pp. 240–5.

- ^ Gardner 2006, annotation 58.

- ^ a b c Clark 1979, pp. 196–7.

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. 11.

- ^ a b Gardner 2006, p. xxx.

- ^ The front page of The Hunting of the Snark (1876) states: "with nine illustrations by Henry Holiday". The assumption is that the "Ocean Chart" (aka "The Bellman's Map") has been arranged by Carroll. Source: Howick, Doug (Winter 2011). "A perfect and absolute mystery". Knight Letter (87): 5. ISSN 0193-886X.

- ^ "Concept draft". shows a redrawn image from a concept draft by C. L. Dodgson (a.k.a. Lewis Carroll). The drawing was part of a lot consisting of an 1876 edition of the "Hunting of the Snark" and a letter (dated 1876-01-04) by Dodgson to Henry Holiday. The lot was auctioned by Doyle New York (Rare Books, Autographs & Photographs – Sale 13BP04 – Lot 553) offered in November 2013.

- ^ Demoor, Marysa (2022). "Surrealist Entanglements (chapter 7)". A Cross-Cultural History of Britain and Belgium, 1815-1918: Mudscapes and Artistic Entanglement. Palgrave MacMillan / Springer nature. pp. 184 to 186, 194, 199 (footnote 20). doi:10.1007/978-3-030-87926-6. ISBN 978-3-030-87926-6.

- ^ Kluge, Goetz (December 2017). "Nose is a Nose is a Nose". Knight Letter (99): 30~31. ISSN 0193-886X. "Author's page".

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Gardner 2006, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b c Gardner 2006, p. 73.

- ^ Carroll, Lewis. "An Easter Greeting to Every Child who Loves "Alice"".

- ^ a b c d Greenarce, Selwyn (2006) [1876]. "The Listing of the Snark". In Gardner, Martin (ed.). The Annotated Hunting of the Snark (Definitive ed.). W. W. Norton. pp. 117–147. ISBN 0-393-06242-2.

- ^ a b Clark 1979, pp. 198–9.

- ^ a b Williams, Sidney Herbert; Madan, Falconer (1979). Handbook of the literature of the Rev. C.L. Dodgson. Folkestone, England: Dawson. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7129-0906-8. OCLC 5754676 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. 22.

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. 37.

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. 34.

- ^ a b Gardner 2006, p. 35.

- ^ Nordheim, Arne. "Nordheim list of works". Arnenordheim.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ "NYNDK | The Hunting of the Snark". All About Jazz. 13 December 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ "La Chasse au Snark". Centre de documentation de la musique contemporaine. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Internet Movie Database: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt22171734/

- ^ DaVison, Simon (April 2023). "The Hunting of the Snark: a New Film Adaption". The Snarkologist. Vol. 1, Fit 5. pp. 34–35. ISSN 2564-0011.

- ^ a b Gardner 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. 42.

- ^ Wilhelm, Kate (1984). Listen, listen. New York, NY: Berkley Books. ISBN 0-425-07327-0. OCLC 11638445.

- ^ Lewis, C.S. (1943). Perelandra. Cosmic Trilogy. London, UK: The Bodley Head. p. 14.

- ^ Lacob, Jace (5 July 2012). "'Inspector Lewis' on PBS's 'Masterpiece Mystery': TV's Smartest Sleuths". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^

Bill Mears (30 June 2008). "Court cites nonsense poem in ruling for Gitmo detainee". CNN. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

A federal appeals court has slammed the reliability of U.S. government intelligence documents, saying just because officials keep repeating their assertions does not make them true.

- ^ Mermin, N. David (1990). Boojums all the way through: Communicating science in a prosaic age. Cambridge University Press. p. xii. ISBN 0-521-38880-5.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (1976). "Mathematical Games". Scientific American. Vol. 4, no. 234. pp. 126–130. Bibcode:1976SciAm.234d.126G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0476-126.

- ^ Andréassian, Vazken; Le Moine, Nicolas; Mathevet, Thibault; Lerat, Julien; Berthet, Lionel; Perrin, Charles (2009). "The hunting of the hydrological snark". Hydrological Processes. 23 (4): 651–654. Bibcode:2009HyPr...23..651A. doi:10.1002/hyp.7217. S2CID 128947665.

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. xxv.

- ^ "For the Snark was a Boojum, you see". Ghost Hound. Season 1. Episode 13 (in Japanese). 2008. WOWOW.

- ^ "Half-Life enemies". GameSpy. IGN Entertainment. Archived from the original on 10 April 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ "Enemies". Down the Rabbit Hole. Gameinfo. Gamespy. Archived from the original on 6 April 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Masters, Marc (2007). No Wave. Black Dog. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-906155-02-5.

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. 70.

- ^ Lennon 1962, p. 243.

- ^ Kelly 1990, p. 27.

- ^ Guiliano, Edward (1987). "Lewis Carroll, laughter and despair, and the Hunting of the Snark". In Bloom, Harold (ed.). Lewis Carroll. New York, NY: Chelsea House. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-87754-689-4.

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. xxiv.

- ^ Cohen 1995, p. 410.

- ^ Cohen 1995, pp. 400–1.

- ^ Lennon 1962, p. 241.

- ^ Kelly 1990, pp. 66–7.

- ^ Snarkophilus Snobbs (pseudonym of F.C.S. Schiller). "A Commentary on the Snark". The Annotated Hunting of the Snark, the Definitive Edition (reprint ed.).

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. xxxvi.

- ^ Gardner 2006, pp. 37–8.

- ^ Shaw, Larry (September 1956). "The Baker Murder Case". Inside and Science Fiction Advertiser: 4–12.

- ^ Gardner 2006, p. 69.

- ^ Graham-Smith, Darien (2005). Contextualising Carroll : the contradiction of science and religion in the life and works of Lewis Carroll (Ph.D.). Bangor: University of Wales.

- ^ Gardiner, Karen (July 2018). "Life, Eternity, and Everything: Hidden Eschatology in the Works of Lewis Carroll". The Carrollian (31): 25–41. ISSN 1462-6519.

- ^ Kluge, Goetz (July 2018). "Burning the Baker". Knight Letter (100): 55–56. ISSN 0193-886X. ("Author's page".)

- ^ British Museum, curator's comment on the print Faiths Victorie in Romes Crueltie: "This is one of a number of earlier prints used by Henry Holiday in his illustrations to Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark, 1876"

Bibliography

[edit]- Carroll, Lewis (1876). The Hunting of the Snark, an Agony in Eight Fits. with nine illustrations by Henry Holiday. Macmillan and Co. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Carroll, Lewis (2006) [1876]. Gardner, Martin (ed.). The Annotated Hunting of the Snark. illustrations by Henry Holiday and others, introduction by Adam Gopnik (The Definitive ed.). W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-06242-2.

- Carroll, Lewis (1898). The Hunting of the Snark, an Agony in Eight Fits. illustrations by Henry Holiday. The Macmillan Company. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- Clark, Anne (1979). Lewis Carroll: A Life. New York, NY: Schocken Books. ISBN 978-0-8052-3722-1. OCLC 4907762.

- Cohen, Morton N. (1995). Lewis Carroll: A Biography. Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-62926-4.

- Kelly, Richard (1990). "Poetry: Approaching the void". Lewis Carroll. Boston, MA: G. K. Hall & Co. ISBN 978-0-8057-6988-3.

- Lennon, Florence Becker (1962). The Life of Lewis Carroll: Victoria through the Looking-Glass. New York, NY: Collier Books. ISBN 0-486-22838-X. OCLC 656464.

Further reading

[edit]- Faimberg, Haydée (2005) [1977]. "The Telescoping of Generations: "The Snark was a Boojum"". Reading Lewis Carroll. Psychology Press. pp. 117–128. ISBN 1-58391-752-7.

- Schweitzer, Louise (2012). "In about one fourth of Schweitzer's doctoral thesis, several chapters are dedicated to The Hunting of the Snark (page 197 to 257)". One Wild Flower. London, UK: Austin & Macauley. ISBN 978-1-84963-146-4.

- Soto, Fernando (Autumn 2001). "The Consumption of the Snark and the Decline of Nonsense: A medico-linguistic reading of Carroll's "Fitful Agony"". The Carrollian (8): 9–50. ISSN 1462-6519.

External links

[edit]- Carroll, Lewis. The Hunting of the Snark. – downloadable formats from Project Gutenberg

- "The Lewis Carroll Society".

Rhyme? And Reason public domain audiobook at LibriVox – collection in which the poem appears

Rhyme? And Reason public domain audiobook at LibriVox – collection in which the poem appears The Hunting of the Snark public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Hunting of the Snark public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Carroll, Lewis. "The Hunting of the Snark in HTML with original illustrations". Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. – "mirrored and extended version, with line numbering". "copy of Carroll's original dedication to Gertrude Chataway"., and "Carroll's Easter greeting".

- "The Hunting of the Snark in BD form, with commentary for each stanza".

- Andresen, Herbjørn (2008). "Illustrators of the Snark".

- Tufail, John (2004). The Illuminated Snark (PDF).

An enquiry into the relationship between text and illustration in The Hunting of the Snark

– 36 pages., (see pg. 29 for examples of the usage of simulacra) - "Catalogue of the main illustrated editions of The Hunting of the Snark".

- "High resolution scans". – from woodblock prints provided by the Christ Church Library

- "Holiday's illustrations and the "Ocean Chart"". – high resolution scans from an original 1876 edition

- "Lewis Carroll resources". – website with textual analysis, bibliography and catalogue of illustrators

- "The Institute of Snarkology". – website for organisation devoted to the study of the poem and snark-hunting.